Category: Stories In Focus

April 23, 2015

Stories In Focus, Reviews, Stories In Focus

Recommended Record: Passion Pit’s Kindred

Eclectic indie pop band Passion Pit released their third album Kindred this past Tuesday, full of vibrating, bubbly synth and…

April 23, 2015

Stories In Focus

Supernovas: Joel VanderWeele

Supernovas: Past Editors-In-Chief Reflect On The STAR and Beyond After graduating from Houghton with a double major in Math &…

April 23, 2015

Stories In Focus

Supernovas: Monica Sandreczki

Supernovas: Past Editors-In-Chief Reflect On The STAR and Beyond I’ve reported stories and hosted our news show, Morning Edition, for…

April 23, 2015

Stories In Focus

Supernovas: Sarah Hutchinson

Supernovas: Past Editors-In-Chief Reflect On The Star and Beyond I was a wet-behind-the-ears, wide-eyed freshman wandering around the campus activities…

April 16, 2015

Stories In Focus, Reviews, Stories In Focus

A Night of Willards, Films, and Fancy Outfits

9th Annual Film Fest Celebrates Veteran and Amateur Filmmakers Alike 2015 marks the ninth consecutive year that Houghton has hosted…

April 16, 2015

Stories In Focus

A Sodexo Story: Pam Wilkinson

Since the fall of 2009, Pam Wilkinson has worked as a Sodexo greeter in the dining hall where she scans…

April 16, 2015

Stories In Focus

Houghton Movement and Arts Center

Local Dance Studio Offers Opportunities for Aspiring Dancers of All Skill Levels In September of 2011, after living in Houghton…

April 09, 2015

Stories In Focus, Reviews, Stories In Focus

Blast From The Past: Lost in Translation Review

Hotels are neutralizing. They exist as these in-between purgatorial vacation places, where you can pretend to live without the nagging…

April 09, 2015

Stories In Focus

Houghtons Only Accounting Professor To Retire

When Lois Ross first joined the Houghton faculty in fall of 2008, she wasn’t anticipating that within two years the…

April 09, 2015

Stories In Focus

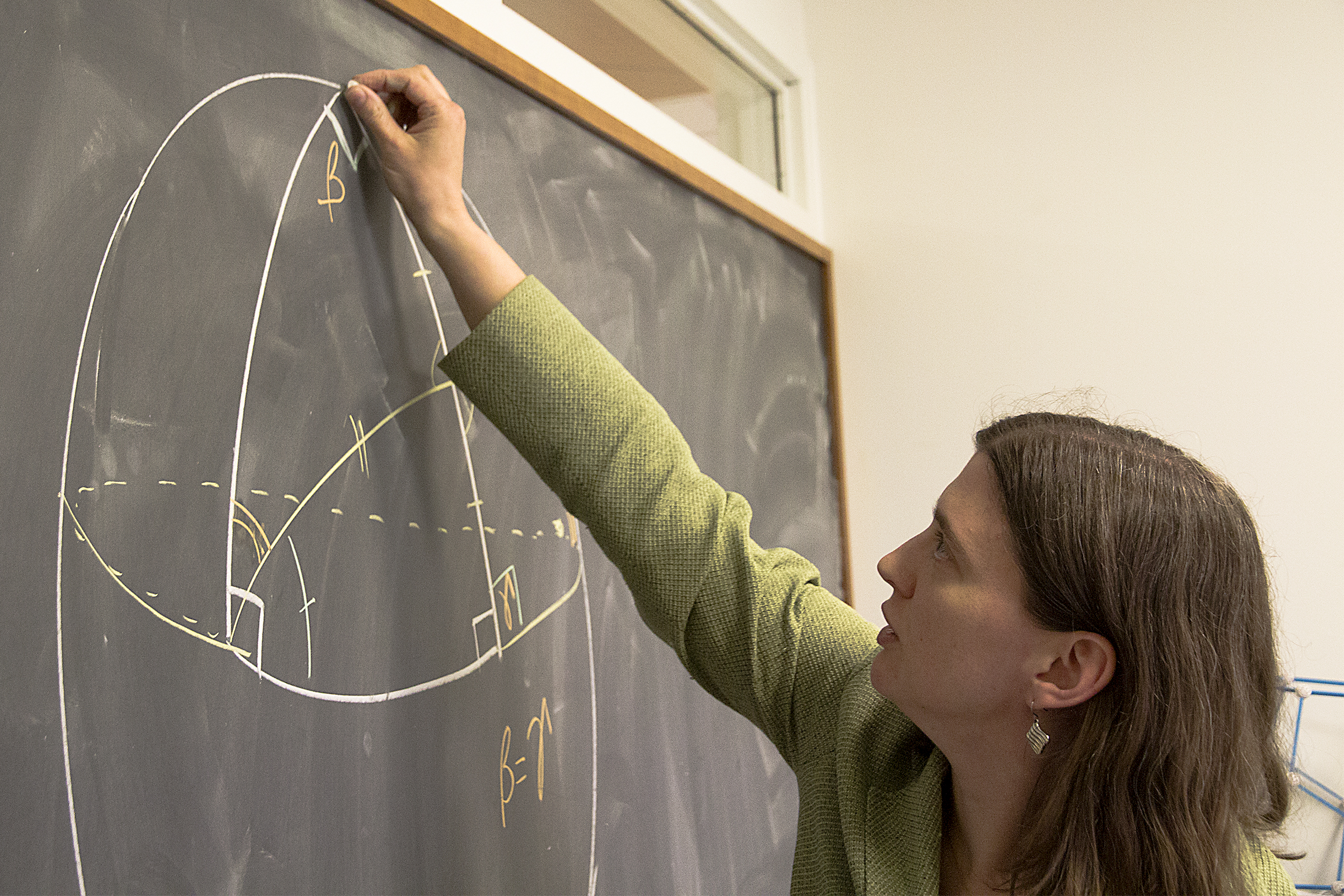

Mathematics Professor Parts From Lifetime Houghton Connection

Camenga Makes the Difficult Decision to Leave Houghton. Though Kristin Camenga was not a Houghton student, she has always felt…